I don’t typically post about work, but then this isn’t really “about work” – it’s me wrapping my head around something. No offense, but you’re sorta along for the ride.

A few years back – as the pandemic was loosening its grip on the world – I had left Amazon, and was happily “bumming around London,” when I got a note from a Amazonian colleague. He had taken a new role at a company I’d never heard of, and wanted to chat about working together again. Over breakfast.

“Breakfast sounds great,” I said, “but I’m not really looking for a job right now.”

After breakfast, and video chats with a couple other folks, I flew to Seattle for what turned out to be the first on-site interview most of my panel had done since the pandemic. Looking for it or not, it seemed a new thing had found me.

When Axon extended an offer and asked me to join I couldn’t delay any more, I had to really decide what I thought about the company and its products.

My decisions about where to work, and what to work on, have always been guided by a few rules, the top one being “I don’t want my code to kill people.” When I had the chance, early in my career, to work on medical device software I decide not to – because I didn’t like the idea of my code killing people by accident. And I’ve never chosen to work on things that kill people by design, like weapons systems.

When Axon was founded, 30-odd years back, it wasn’t called Axon – and it didn’t do software. It was called TASER, and that’s mostly what it did. The TASER is a weapon, no matter how you slice it. A “less lethal” one for sure, but a weapon. I wouldn’t be joining to work on TASER – I’d be working on real time and situational intelligence tools for first responders – but TASER was a proverbial elephant in the room.

So I think it’s fair to say that the decision to join Axon was one of the most carefully considered career choices I’ve ever made.

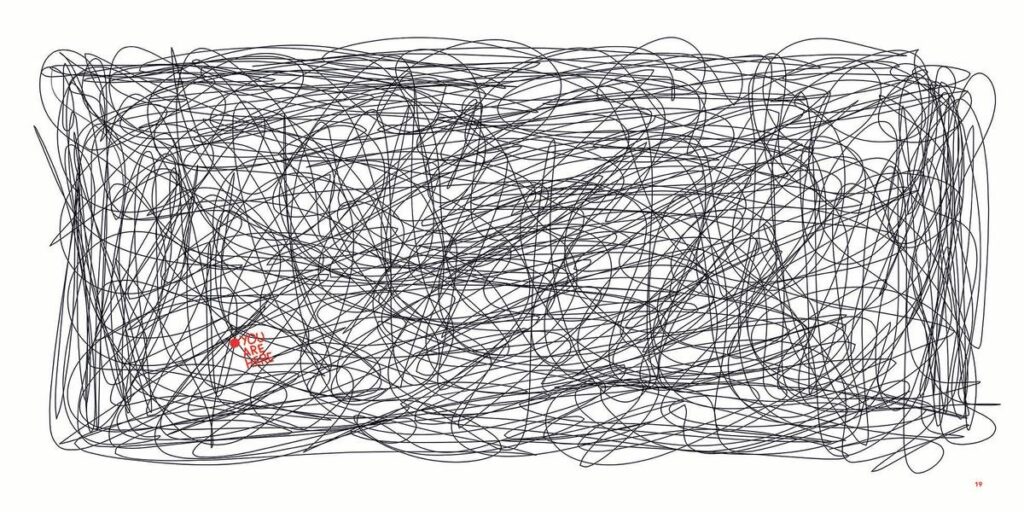

I turned the decision over and over. Stared at it from every angle. I talked to friends. I got input from people I expected would tell me why joining was the stupidest thing I could do, and from people I guessed would argue the opposite. I didn’t always get what I predicted. I looked into the company. Its founder. The things they built. The customers they built those things for…

Ultimately, I decided that as much as I wish law enforcement didn’t need TASERS – or firearms – the TASER seemed like a tool that could make things better. And making things better seemed… better.

I’ve told bits of that story to hundreds of the candidates I’ve interviewed since joining. I’ve encouraged them to think about the implications of working on systems that are mission critical – and sometimes safety or life critical. One of the senior leaders sometimes calls it a “sacred responsibility,” and while I might choose different words, I understand and agree with the sentiment. The responsibility, and the associated ways of working it encourages, aren’t a good fit for everyone. They demand thinking critically about choices and tradeoffs, and being willing to fly in the face of commonly accepted industry best practices – what’s right for selling consumer goods and services, or selling advertisements and sharing cat pictures on the internet, isn’t clearly right for building systems people rely on to keep themselves and others safe. Moving fast and breaking things is a terrible idea when it puts people in harm’s way.

My time at Axon has taught me a bunch.

About public safety, and the people who choose to walk that path.

About the tools we ask first responders to use while doing their jobs.

About how it feels to go 70mph – the wrong way on a 20mph street – in the back of a Met patrol car, lights flashing and siren screaming. Whenever I think “I’m a pretty good driver,” I’ll think about the police constable who was weaving the patrol car through impossibly tight spots that I swear didn’t even exist until he was in them; and for whom this race through London toward danger was just a Tuesday…

And along the way, I learned some things about myself.

Three years on Axon and I have reached a fork in the road, and our paths are diverging.

There’s no one simple reason. The London R&D center I joined to help grow from nothing has grown – to over a hundred in and around London. And the company continues to grow globally year over year. What a company needs changes as it grows. And I started getting the distinct feeling that what I’m good at – and the ways I most enjoy contributing – were falling out of alignment with the company’s needs.

I was growing less and less confident that I was in the right place, doing the right things, right now.

I still looked for ways to stay. I worked with leadership to create a new role that we were optimistic I’d be both happy and effective in. Sadly after the first couple months in that role it was clear to everyone it wasn’t going to work out as hoped.

I tried to convince myself there was at least one more viable thing to try, but evidence was piling up that I was trying to fit a me-shaped peg into a someone-else-shaped hole.

In retrospect, perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised that deciding to leave was just as difficult as deciding to join. But it was difficult, and I was surprised. Deciding to quit was hard, for a bunch of reasons – all the “normal” ones, and some I struggled to put words around.

Lots of companies have a mission statement. They hang it on a wall in a lobby, or the executive offices. They trot it out in shareholder letters, or during shareholder meetings.

Axon has a mission.

An audacious and seemingly impossible mission. We’re out to obsolete the bullet, and incredibly, impossibly, we’re actually making progress.

(I know, it sounds impossible, or maybe just charmingly naive. I've become convinced it's neither of those. Axon's founder and CEO Rick Smith talks about the company, the vision and the mission with Joubin Mirzadegan in this episode of Grit - give it a listen, see if he convinces you, too.)

And I had no idea, when I joined, how much having “a mission that matters” would matter to me.

Still, that didn’t change the situation on the ground, and failing to find a better path, I handed in my notice.

I’m parting ways with some great colleagues, and folks I hope to keep as friends. And I’m leaving a company I feel more emotionally invested in than most anything else I can point at in my career.

I don’t yet know what comes next. Some time off, catching up on things work displaces in life. Hopefully more travel.

And if I’m very lucky at some point the next thing will find me. Again.

I want Axon to succeed in its mission to Protect Life, and I think the best way I can support that right now is to help Axon find people who contribute to that success.

So if you or someone you know are looking for a place to have outsized positive societal impact, and are based in Seattle, San Francisco, Phoenix, Atlanta, Boston, London, Brussels, Tampere, Ho Chi Minh City, or anywhere Axon has a hub, drop me a line. I’m more than happy to make introductions.